Desert Island Books

Desert Island Books

Revd Graham Hunter, Vicar of St John's Hoxton, writes:

I recently had a conversation with a friend who was looking to do some reading over the coming months to help with the growth and development of her own faith. The friend in question is pursuing a career as an academic, and finds that most of her reading is directed towards her particular subject area of interest - biblical studies. I mentioned to her that there were a few books which have had a profound influence on my life and the development of my Christian faith: some books of theology, some devotional books, and some novels.

I thought I would write for her (and anyone else interested) a ‘Desert Island Books’ blog with my top 7 books that have profoundly shaped me. I’ve listed them in the order that I recall reading them. I’ve offered a very brief summary of the book - but chiefly focused a few lines on the impact the book had on me. (You’ll note that I’ve listed 6 books below - I can’t decide on the 7th just yet - but I’ll update the blog when I have!)

(I’ve created an Amazon list with links to all these books. Other booksellers are available!)

Evangelical Theology: An Introduction - Karl Barth

I read Evangelical Theology sometime around the year 1999-2000. I was studying theology at King’s College London, and realised the influence of Barth’s theology upon many of my tutors: Colin Gunton, Michael Banner, Murray Rae and Steve Holmes to name a few… (Appropriately) intimidated by Church Dogmatics, I turned initially to Evangelical Theology to get a taste of Barth’s approach. I was astonished by what I found. For the previous 7-8 years since I had become a Christian, I was accustomed to church leaders speaking of the bible as being the revealed word of God. In fact, in one of the churches in which I worshipped, it was joked that we believed in Father, Son and Holy Scripture. A conservative, and foundationalist (not that I understood then what this meant) approach to scripture was all I knew. And yet my early experience of formal theological study introduced me to textual criticism - and resonated with the approach of literary criticism that I had already encountered in my schooling. I was worshipping in a charismatic evangelical church in which many members were sceptical about the benefit of theological study - worried that faith might migrate from the heart to the head! I was experiencing some disenchantment with the culture of evangelicalism in which I stood - and I wasn’t sure whether I could claim the term ‘Evangelical’ as applying to myself anymore. This was all a bit overwhelming and dislocatiing - and then I read Barth!

In this short volume I suddenly encountered a theological framework which unashamedly declared Jesus to be the revealed Word of God - and thus the object and source of all theological method. This made sense to me doxologically, but also allowed me to view the bible now as the ‘witness’ to the self-revelation of God in Christ. Scripture was a prophetic and apostolic witness to Jesus - to God’s work of creation, redemption and reconciliation. The scriptural witness shaped and informed the community, and indeed derived its authority from both the community and the Spirit. All of a sudden I had a ‘system’ - a scaffold on which to support my theological learning. And it was dynamic! Because the eternal word of God - Jesus Christ - who is raised from the dead and seated at the right hand of the Father was at the centre, there is an intrinsic dynamism to all theology. Our theological claims cannot rest on any human foundations - but rather look simultaneously backwards and forwards to the person and work of Jesus.

Conflict, Holiness & Politics in the Teachings of Jesus - Marcus Borg

I read this book for a New Testament module assignment as an undergraduate. Central to the argument of the book is that Jesus’ actions in his healing ministry and also in table fellowship should be interpreted as political actions set in contrast to the prevailing culture of his environment. Borg argues that the Pharisees interpreted Jewish ‘holiness’ as consisting chiefly in the avoidance of any form of syncretism so as to avoid being ‘defiled’ by gentile influence. Holiness was separation from Roman culture. By contrast, Jesus reinterprets ‘holiness’ as being expressed in acts of mercy. Far from defiling himself when he touches a man with a withered hand, or eats with tax collectors and sinners, rather divine holiness flows from him in his acts of mercy and makes the ‘unclean’ clean. It effected in me a paradigm shift in terms of how I saw the church’s engagement with mission in the world around us. I had always sat uncomfortably with the low-church evangelical tradition’s tendency towards quietism and pietism - but this gave me a proper biblical argument for radical, merciful, political engagement in the world. As I later encountered Niebuhr’s work on Christ and Culture, I realised that I had a framework for how Jesus ‘transforms’ culture - by merciful engagement that brings holiness. Jesus has the real, and unfated, Midas touch!

Resurrection - Rowan Williams

If I remember correctly (and I can’t check because I’ve lent my copy of the book to someone!) this was written in 1984. I read it around 2002 as part of my Easter devotional time that year. I had met Rowan Williams in February 2002, when he came to lead a quiet day at my church, just shortly before being announced as the next Archbishop of Canterbury. (In fact, I sat next to him for lunch at the Vicarage that day - and feel as though I sat next to holiness…) This book is a theological reflection on the Easter narratives in the gospels - and are amongst the most comforting and disturbing reflections I’ve ever read on the resurrection of Jesus. A few motifs made a lasting impression:

First, that we may not look to the crucified Christ as the one who vindicates us in our suffering, or who validates us in our victimhood. Rather, we follow the resurrected Christ who appears to us as a stranger - who leads us through and beyond our suffering into new life. Therefore we may not wallow! Everything can be redeemed and renewed.

Second, that as much as we have suffered violence and injustice in our lives - being the victims of sin - we have also been agents or perpetrators of oppression and violence towards others. We take our place in the crowd that shouted crucify, and we do the same to others. This is an uncomfortable challenge - and refuses us the role of hero within our own stories.

Third, and this relates to both preceding points, forgiveness is the gift of true memory - by which we can face our past with truthfulness and honest appraisal, knowing that we have been wounded by others, but also that we in turn have wounded others. Forgiveness is the grace to experience not just reconciliation to God in Christ, but also reconciliation to our past, present and future selves because we know that in Christ, God is lovingly and redemptively present to every moment of our lives. The pastoral implications of this are huge!

Here’s a taste:

‘God is the agency that gives us back our memories, because God is the ‘presence’ to which all reality is present. We have already begun to see how the returning of memory is very far from being a congenial and painless process, because memory is the memory of our responsibility for rejection and injury, for diminution of self and others. And yet the refusal or denial of memory is likewise diminution, perhaps the deepest diminution of all. If the whole self is the concern and the theatre of God’s saving work, then the past of the self must be included in the scope of this work.’

In The Name Of Jesus - Henri Nouwen

I read this book on retreat in 2003 and it has become for me perhaps the most important book expressing the nature of Christian leadership. The book is based on 3 short talks that Henri Nouwen gave at a conference - consequently, the font size is big, the line spacing large, and the chapters short! You can read this book in one sitting with a pot of coffee - but you’ll want to re-read it several times as you meditate upon its message.

Nouwen uses the temptation narrative as his springboard, and explores three key temptations for anyone embarking upon Christian leadership: to be relevant, to be popular, to be powerful. He explores how these take hold of us in Christian ministry, and how we may rebuke the temptations if we are to truly reflect the image of Christ in our interactions with others.

Nouwen is movingly vulnerable about his own life, and speaks of how he becomes aware of ‘the extent to which my leadership was still a desire to control complex situations, confused emotions, and anxious minds… It seems easier to be God than to love God, easier to control people than to love people, easier to own life than to love life…’

Here’s another taster:

‘The long painful history of the church is the history of people ever and again tempted to choose power over love, control over the cross, being a leader over being led. Those who resisted this temptation to the end and thereby give us hope are the true saints.’

My Name Is Asher Lev - Chaim Potok

I read this novel sometime around 2004-05 and it moved me to tears. It spoke deeply to the human need to belong to community, but also to the pain that our communities and families may cause us and our yearning for redemption and healing.

Set in 1970s New York, Asher Lev belongs to a strict Orthodox Jewish community - and a family whose bond is created and preserved by remaining passionately set part from and opposed to the wider social and cultural environment. Asher Lev discovers his gift and passion for art - visual art, drawing and painting specifically. But this artistic work of expression and depiction is frowned upon and even forbidden within his community. There is no space for him to express himself within the acceptable artistic vocabulary of his religious identity. The book builds in a crescendo to the point at which Lev creates a piece of art - the Brooklyn Crucifixion - in which he is forced to draw upon Christian traditions in art to depict his pain and suffering along with his hope for redemption.

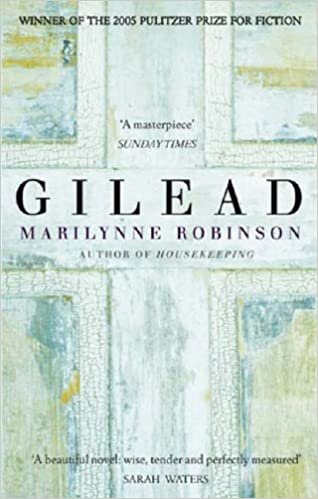

Gilead - Marilynne Robinson

Gilead is an extraordinarily moving account of the life of an ageing minister, John Ames, and the life of his ageing town, Gilead. Ames, along with his father before him, had ministered in the local Presbyterian / Congregational church for something approaching 80-100 years between them. Ames’ grandfather had also lived in the town, and had been involved in the underground railway during the American civil war.

The novel is set roughly in 1960s-70s America, and takes the form of a series of letters written by Ames to his young son. Aware of his inevitable ageing and the prospect of his death, Ames seeks to explain to his son - who is still a boy in childhood - something of his life and ministry, and something of the town's history. Ames’ reflections on life, friendship, community and change - as well as the growth and development of his own Christian faith - are breathtakingly moving.

In one of my favourite passages, he reflects on what it means to pronounce a blessing on something or someone. Ames exhibits a sense of wonder for God's creation - and has a deep care for the variety of God's human creation. He loves to reflect theologically, and is quite clearly Barthian in his approach. You can learn a great deal about the 19th century liberal theological enterprise and Barth's response just by reading this novel!

John Ames has become something of a role model for me on how to be human: to be kind, compassionate, serious, gentle, and to hold everyone and everything in deep and profound reverence - as the world around us reflects and reveals the image of God.